Lessons from a Conquering Zero

My unorthodox quest to DNF Ultra Trail Snowdonia

The high mountains of Wales, the “Welsh 3000s” as they’re known, are wild, craggy rocky beasts. Their trails are technical, full of scree fields and scrambles. Imperceptible trods link them through tufty bogs. All the while, the impetuous Welsh weather lies in wait, ready to blow a hooley.

Yet crowds flock to Eryri in their droves. Its panorama is, in a word, epic. Whether bathed in sunshine, or immersed in menacing cloud, the brazen drama of the scenery draws one in like a moth to a light. It simply begs to be explored.

This enigmatic landscape is the theatre of dreams on which the 100 mile Ultra Trail Snowdonia plays out.

UTS describes itself as “the ultimate grand-tour of Eryri”, taking in the likes of Cnicht, the Glyders, Carnedd Llewelyn, Hebog, Siabod and Snowdon (twice, no less). You’d be hard pressed to experience more of this region in a single run.

Being a UTMB race, UTS does bestow on its finishers a number of Running Stones. Happily, I had an abundance of these little activity pebbles in my wallet already, so my interest in UTS was purely in the play itself.

Eryri’s theatre of dreams beckoned. The stage was set. Open the popcorn and ensure you’re sitting comfortably, because the first act of this aleatory farce is about to begin.

Everything Was Going So Unwell

Avid readers may recall I’d run the 268 mile Winter Spine just a few months prior. While I emerged fairly unscathed, I faced an uphill battle to rebuild fitness in time for UTS. Other commitments meant I couldn’t train hills or technical terrain, but I did at least build up to a few weeks of reasonable mileage, giving me some cause for optimism.

This only grew as, with a fortnight to go, one thing after another fell into place. My brother offered to crew me. I squeezed in a rollicking recce of Moel Siabod with my friend Steve. A cobbler resoled my shoes with Vibram Megagrip, giving me a fighting chance over those mighty slippery rocks. Fitness aside, I was really looking forward to UTS.

One week out, I fell ill with something particularly nasty. After enduring a horrific night, my body fought back swiftly, and by the following day I felt much better. But would I be well enough to race?

What I had going for me was having my brother as crew. He’d transport me to Wales, and get me to the start line. All I had to do between now and then was recover. There might be just enough time.

Two days before UTS, my brother called to say he’d contracted some sort of illness. From what I could hear over the phone, it sounded pretty nasty. He’d still be there to crew, he insisted, but thought I might want to travel up separately. Not enthralled with the prospect of fighting a second illness, I agreed that might be best.

I was well past the contagious stage myself, but I still felt less than 100%. With my crew now on half duties (and I wasn’t too confident about that), was running UTS this year going to be a sensible move?

Nonetheless, later that evening, I started planning my kit, and drafting a crewed nutrition plan. This dragged on late into the night, until headache fused with fatigue, and many questions went unanswered.

The following morning, I woke feeling both tired and poorly. I’d planned to leave for my B&B by 10am, and it was already past that. I hurriedly rebooted my gear and nutrition preparations, but under time pressure, I had to draw the line and just pile everything into the car.

I couldn’t think of anything I fancied less than the 4+ hour drive ahead of me.

Many hours late now, I was about to depart when my brother called. His sniffles had gotten much worse, and he wasn’t “entirely confident” he’d still be able to crew me, he expressed through an explosion of coughs and croaks. Never mind driving to Wales and crewing me for 30 hours straight, it sounded like he’d struggle to roll over in his sick bed!

The news didn’t come as a great surprise, but it did leave me standing in my driveway, at a loss for what to do. Questions spun around my tired, headachy brain. What should I do with all the crew bags I’d prepared. Should I just transfer all the nutrition into my race vest? Where on earth would it go, I’d surely need to take a larger pack? What about the real food I’d planned, and what did it all mean for my nutrition strategy? What kit should I to move into my drop bag? Hadn’t I registered for race parking using my brother’s car numberplate?

I glanced at my watch, and fortuitously that draw all the questions to a neat close. It was so late that if I didn’t leave now, I needn’t bother at all.

I dashed back inside to grab yet another box of gels and threw it in the boot, as if that’d solve all my problems. Back in the car, I ran my hands around the steering wheel, feeling its stitching. What did I think I was doing? I couldn’t run 100 miles feeling like this.

Maybe not, I thought. But I could at least run some of it.

Mountain Recrew

As I wended my way along the windy Welsh roads, head slightly throbbing, I found it strange that the car in front of me bore a striking resemblance to my friend Jan’s. Come to think of it, he had mentioned he might come to spectate.

It wasn't long before my car speakers crackled into life to read a voice message: “Are you behind me?” We pulled over in a lay-by, and celebrated the implausible coincidence of our meeting like this.

I explained to Jan that I was down a crew; that I was still feeling under the weather, and might not actually run the race. Jan, being all too familiar with my determined nature, didn’t think it likely that I’d just travelled up here to twiddle my thumbs and spectate. He immediately offered to crew.

Seconds later, like military commanders planning a counter-offensive, we had paper maps draped over our car bonnets, and were frantically annotating them with checkpoint details and ETAs. In the space of 5 minutes, a fresh crew plan had emerged, and the race was back on.

Jan scooted off to Snowdon to catch the sunset from the peak, while I settled into my B&B and headed to bed. I felt immensely fortunate and privileged to have picked up a new crew. But what exactly were my intentions here?

I’d just run the first checkpoint or two, I concluded. I’d experience some of the UTS atmosphere, enjoy the glorious weather that was forecast, and DNF before I made myself any worse. It’d be the best of both worlds.

The morning did indeed bring the most fabulous weather. The latest forecast showed scorching conditions lasting the entire duration of the race. This was exactly what I’d dreamed of for UTS, before my illness…

Race registration was a breeze, after which I met back up with Jan, and my friend Steve, with whom I’d recced Moel Siabod a fortnight prior.

While waiting for the start, I reiterated my plan to myself. I was going to run for a little while, and then DNF somewhere between CP2 and CP7 (the midway point). I’d enjoy some of the UTS experience, without impacting my recovery. It sounded sensible enough to me.

The Race Is Half On

I positioned myself four or five rows behind the starting line. The UTMB arch loomed large ahead of me, while the imposing form of Llanberis’ Slate Museum screened the rear. I spotted Mark Derbyshire a couple of places in front of me, but a few rows back from the starting line. Modest as ever.

The countdown started, and we were off. Boy, were we off!

Compared to many UTMB races that head straight into long singletrack climbs, where it’s easy to get caught behind hoards of slower runners, UTS was a breath of fresh air. The streets of Llanberis are wide and traffic-tree, affording plenty of room to manoeuvre and find one’s place before the long climb up Snowdon via the Llanberis Path, which is almost as wide as a track itself.

I attacked the climb at a decent clip. There were a few reasons for this. First, I wanted to make good progress before the sun hit its peak & things got too toasty. Second, I knew I'd struggle over the more technical terrain, of which there was going to be plenty after Snowdon. And third - I was going to DNF shortly anyway, so there was no point in hanging around.

I climbed up to Bwlch Glas, the turning onto the Pyg track just shy of Snowdon summit, in 65 minutes. Not bad going for the start of a 100. I didn't feel too bad at this point, but conditions were already getting pretty warm. Especially in my present state, I could tell this was going to be a complicating factor.

I’d climbed up the Pyg track a couple of times, but never descended it before. I found it really runnable in this direction. Nonetheless, coming from the flatlands of Hertfordshire I still class this as mildly technical in places. I was unsurprised to see a steady stream of runners overtaking me on the descent, flying over the rocks like the mountain goat I dreamt I was.

I paused briefly at Pen-y-Pass to refill a water bottle, and dashed straight back off. As soon as I’d left, I realised I'd screwed up: I’d left CP1 half a litre short, and hadn’t added my Tailwind powder.

Also, my throat was slightly sore. That wasn’t good. With a dodgy throat, I really didn’t fancy guzzling down more sugary gels and bars. Yet, that was what formed the bulk of my nutrition strategy. I began to fall behind on my eating schedule.

I felt a bit uneasy climbing Glyder Fawr, as I couldn’t find any of UTMB’s route signage for a while, and the GPX didn’t match any of the trods I could find. Runners behind me followed my lead; so either the signage was missing, or half the field followed a clueless guy with a headache.

The descent took us down Devil’s Kitchen, a particularly steep scree slope. I tried to skid down as efficiently as I could, but my quads still took an absolute pounding.

We skirted Llyn Idwal before cutting back to climb up the saddle between Tryfan and Glyder Fach. The views were absolutely stunning in this glorious weather, and I tried my absolute hardest to enjoy them. After all, these were the UTS conditions I had dreamt of.

But things were quite simply going to pot. I had run out of fluids, and was dehydrating fast. My sore throat was getting worse. That coupled with an unsettled stomach meant I was eschewing all my nutrition, and that was tanking both my energy and my mood. My light headache wasn’t helping matters either.

My decision to start this race was looking more questionable by the minute.

Glan DNF

As I rounded a bend, the welcoming party for CP2, Glan Dena, came into view. I could see a crowd of people atop a small hill politely encouraging the runners down below, exhibiting that typically bashful British disposition and comportment.

Standing proud on a rock in front of them all, gazing out like Columbus from the bow of the Santa María, was a chap occupying an entirely different plane of existence. He was bellowing so loudly that London, Britain, and indeed the whole of the old British Empire could have heard him - except his voice was actually being overpowered by another sound, a clattering of such ear-splitting volume it could have summoned a serpent deity. By shielding my eyes from the sun, I could just make out a wooden rattler in Jan’s right hand, which he was waving around with all the vigour he could muster. If this was a music concert, they’d have shut it down for exceeding the decibel limit. That was my mate, Jan!

Jan is a force of nature, rarely doing anything by halves. If he’s there to support you, then boy is he there to support you, and everyone else. He bounded down to sort out my Tailwind, dowse my cap and try to stuff nutrients into me.

In between bites of a banana, which was something I could actually get down my throat, I ran a sitrep.

I had a headache, sore throat, could hardly eat, was already dehydrated, and was finding it difficult to distinguish my body’s signals between nutritional needs and illness.

While common sense directed me to DNF, that was never seriously on the cards. Not at CP2, not when I was physically capable of continuing. It’s an endurance race, after all. I’d DNF a little farther on, when I was commensurately more broken. That made more sense.

There was no need for me to restock any gels or bars, since I’d hardly eaten any. Instead, I left some of the gels I’d been carrying behind. I might as well save the weight, I reasoned.

Parched on the Carneddau

There was a particularly steep climb up Pen Yr Ole Wen onto the Carneddau ridge, with a decent little scramble around 600-800m a notable highlight. Thankfully this one was really well-signed.

The ridge continued over Carnedd Fach, Dafydd and Llewelyn in a series of gentle undulations. Bathed in the evening sunlight, the ridgeline was a sight to behold. Glancing over my right shoulder, I could see Tryfan looking absolutely resplendent. I recalled seeing the very same sight during Dragon’s Back, moving in the reverse direction.

On this clear day under the setting sun, I should have loved every minute of this stretch. But instead I struggled despondently along it, very low on energy having eaten so little, and growing increasingly dehydrated as I rationed my 1.5L of water in the heat. I knew this would be a long stretch without an opportunity to refill, since CP3 had to be moved out a few kilometres this year. So I just tried to keep some fluids trickling in to ameliorate my throat.

Another change for 2024 was a stipulation that UTS had to avoid the summit of Pen Yr Helgi Du. The route deviation took us along a minor trail cutting across the southern side of the fell. I'd heard this would be one of the more awkward sections of the course.

I found a couple of safety team members waiting at its start, one perched in what looked like a thoroughly precarious position. Squeezing past without knocking him down the fell was the first trick, and the second was safely navigating this little slither of a trail. In places it was worn away entirely and needed a hearty bound to span the gap. This kept my full attention for the duration, which did at least take my mind off of my various ailments.

Finally, the trail rejoined a proper path, before broadening into a wide & dreamy grassy descent. I swigged the last of my water while I floated down the hillside, to intercept a pancake flat path at the bottom.

This was where CP3 should have been. Since they’d been unable to secure land permission this year, I'd have to persevere for a while longer without water.

The first half of the stretch to the relocated CP3 was as simple as they come, with only a series of metal gates to interrupt one’s flow. The second half took us around Llyn Colwlyd. While this had looked fast & flat on the map, the path actually undulated continually through a mix of mud and bog. It was a long old slog, while I and my throat willed this CP3 water stop into existence.

When it came, I was pleasantly surprised. We’d been told this temporary CP would only stock water, but there was a range of Naak nutrition here too. Not that I needed any of it, mind. I was still carrying nutrition from Snowdon. I was just glad for the water refill.

Into the Night

The route south to Capel Curig kicked off slowly with more climbing & thrashing through grassy bogs. As light faded and a runner passed me, I commented that we’d need to don our headtorches pretty soon.

“No, we’ll make it to Capel Curig”, he stated authoritatively.

I raised an eyebrow. While I didn’t know this section of the route, I did know Capel Curig was miles away.

“I’ve recced this”, he explained. “There’s a stretch of technical descent to get through, then a short wood section that might feel a bit dark, but then it’s open and easy. No need for headtorches.” Unconvinced, I let him speed on, while I did my pitiful best over this section with all its rocks and roots.

By the time I reached the wood he’d spoken of, it was properly dark. Under the tree canopy, which supposedly “might feel a bit dark”, it was totally pitch. I shook my head in bemusement, and used the little spotlight on my Garmin watch to illuminate a few metres ahead. After bashing through this heavily rooted path for a few minutes with my arm outstretched, I passed my friend ferreting around in his pack, obviously searching for his headtorch. “Need a light?”, I quipped, stifling a grin.

After the forest, we did indeed reach a road, and then a wide, easy footpath. It looked like my perspicacious compatriot had been right about this, at least - from hereon, we’d enjoy a veritable Autobahn to CP4.

I thought I heard some unusually enthusiastic support up ahead, and sure enough this turned out to be Jan, cheering on runners with gusto. On seeing me, he flailed his wooden rattler with all the energy of a child at an ice cream shop. The vibrations might well have triggered earthquakes in Osaka.

The manicured footpath continued down into Capel Curig. This was a major checkpoint, and one I knew I’d need to utilise if I was going to make any more progress in this race. I simply had to force some food down my throat.

Tunnel Vision

Despite my clear and cogent plan not to leave CP4 before I’d properly refuelled, I pretty much rushed through the aid station. The only thing I stopped for was a piece of bread and a cup of Naak’s “Ultra Energy Salted Soup”, which really was hopeless: an ultra-processed concoction that appeared to be little more than flavoured warm water.

On my way out I spotted a vat of hot food that looked like it could be vegan. I hesitated momentarily… but with my pack back on and already halfway out the door, I made the call to head back on out.

I was keen to get going, I suppose, because I was looking forward to this section over Moel Siabod. I’d recced it a couple of weeks ago, both solo and together with Steve. It’s a simple climb up, followed by a fun, tricky to navigate rocky downscramble, finishing with a boggy trail down to Dolwyddelan. An awkward section; but an exciting one, and even in my poorly state, I was keen to experience it in the dark.

The climb up Siabod went on forever, though. Fuelled exclusively by that thimble of Naak’s weird lukewarm water, I had absolutely no energy in my legs. Meanwhile my sore throat was causing me some confusion. Was it sore because I was under-hydrating? Was it sore regardless, and was I now over-hydrating trying to calm it down? Expecting to DNF, I hadn’t even bothered tracking my electrolyte intake this race.

The night was warm and humid, with very little wind at the summit. I was able to dial in my temperature simply by rolling and unrolling the sleeves on my baselayer. I had to admit, it was a truly awesome evening to be out running.

I struggled to locate any route markers for the downscramble, so relied on my GPX. I tracked it as closely as I could, all the while trying to spot those subtle signs of a travelled route over the rocks.

Being so nutritionally exhausted, my brain wasn’t firing on all cylinders. So I just took it slow and steady down here, keeping on track and ensuring I didn’t do myself an injury.

I managed fairly well (see the track in red). It was pretty close to my recce with Steve (shown in green), and a huge improvement over my solo recce (shown in blue).

From Llyn y Foel, things got easier. We descended through the bog, crossed the river, and skipped down a singletrack over all the tree roots. Taking it easy on the descent had allowed me to regenerate some much needed energy, just in time to put in a shift on the road leading down into Dolwyddelan.

I desperately needed to fuel myself. The only way that was going to happen was with real food, and I just didn’t have any.

Jan met me at the aid station, where I explained my nutritional predicament in more detail. I could see the cogs whirring in his brain. There wasn’t a great deal we could do to manifest ‘real’ plant-based food into existence, not at 1am in the little village of Dolwyddelan. We made do with the solitary bagel I’d included in the crew bag, and a foraged PB&J sandwich from the aid station buffet.

I also took the opportunity to perform a bit of foot care. I’d been trudging through bogs pretty much non-stop since Pen-y-Pass, so my feet had been wet for 10 hours straight. They were beginning to feel uncomfortable, so a 10 minute airing and a change of socks was just the ticket.

There was a long gap until our next scheduled meeting point at CP9 Beddgelert, assuming I made it that far. So I suggested Jan catch some shut-eye. Jan was having none of it though. Instead, he flipped my suggestion 180° on its head, committing to meet me at the very next checkpoint, CP6 Blaenau Ffestiniog. I was too absorbed in my own problems to argue.

When I left the checkpoint, I checked my progress against my own time estimates, which I’d calculated pre-illness (based around running sub-30 hours). I was surprised to see that, despite everything, I was actually running to schedule. That was a mere curiosity though. I’d DNF soon.

The climb up Y Ro Wen went on for longer than I remembered. For the first time in a while, I found myself alone, with no other runners in sight. This is what I prefer, especially at night. An opportunity to be at one with my own thoughts, and have my own unique experience.

At the top, the terrain transitioned back to grassy bogs, and my feet started swimming once again. Keen to get ahead of the deterioration of my feet, I texted Jan to ask for a change of shoes and my waterproof Dexshell socks at CP6. I soon thought better of it, reasoning that we’d be facing another boiling hot day when the sun rose, and thick knee-length socks would be just about as welcome as a knitted jumper and scarf.

It was still dark when I reached the slate quarry to the east of Blaenau, following which there was a short and fast road descent down into the town itself, where CP6 was located.

I still had all my untouched sugary nutrition, and wasn’t drinking much in the relative coolness of the night. Left to my own devices I’d have run straight past the CP, but Jan met me in the car park to funnel me inside.

He’d been busy since we last met. Somehow, at 3am in the middle of remote Snowdonia, he’d managed to find and prepare a plate of rice. A little bland perhaps, but it was real food, which my body and throat was crying out for. Perplexingly, he’d also found a jar of gherkins.

Another sock change and I was back off. There was a road climb up to Llyn Cwmorthin, before I skirted the lake on trail, and wrapped around for the climb up Rhosydd quarry. In daylight this section’s a sight to behold, with the lake behind backed by the Moelwyn range. There wasn’t much to see tonight.

Once up there, it’s easyish going through the abandoned quarry tips, over moorland and onto a thin trail just above Stwlan Dam. Here, the route cuts back onto a steep scramble up to Craigysgafn and Moelwyn Mawr. I’d run this on my recce, and in reverse during Dragon’s Back. Routefinding up the scramble was much harder in the dark though, and I clocked a 25 minute kilometre here.

I knew what was coming next, too. A really steep, direct descent down the west side of Moelwyn Mawr. This proved to be no more fun than it had been on the recce, but at least thereafter there was just a downhill road sprint into CP7 Croesor, where my drop bag was waiting.

Halfway: A Respectable Place to DNF

At 87km and 5300m v+, Croesor is marginally over the halfway point in both distance and vert. I was 17 hours 40 minutes into the race, and 2 hours behind schedule. By the time I ate, aired my sodden feet, sorted out my drop bag, charged my devices, and decided whether to continue, that could easily grow into a 3 hour deficit. That meant I was on for a 36 hour race. Not a time I’d be remotely happy with.

It was time for some serious reflection. I was not entirely well. I couldn’t fuel properly. I couldn’t hydrate properly. I was carrying a miserable pace over technical terrain, mainly because my headachy brain was working too slowly to plan my foot placement far enough in advance. I wasn’t performing well over the short sections of non-technical terrain either, due to my nutritional deficiencies. I was having an objectively unpleasant experience. I couldn’t articulate what I was hoping to get out of this. And I was wasting Jan’s time - although, he seemed to be loving every minute.

Yet, just like at CP2, pulling the trigger and throwing in the towel felt like a really big decision. I decided to eat first.

The aid station staff brought me a bowl of tinned vegetable curry and rice. This was a huge improvement over Naak’s ‘Salty Soup’ from CP4, but still a far cry from the freshly cooked food you get at many of the independent British ultras.

Behind me, another competitor was DNF’ing, and enquiring about transport back to Llanberis. I bit my tongue, restraining myself from joining him. After all, I’d eaten now. My feet were dry again. It’d be light soon, and the sun would come out. All I had to do was get myself over Cnicht, and I’d be at CP8. Only a stone’s throw from race HQ at Llanberis. DNFing there would be easier logistically, I told myself.

And with that basically random decision, my most likely opportunity to DNF slipped through my fingers.

Chasing the Dragon

As the sun rose and another glorious day dawned in the Welsh mountains, I started my journey to CP8.

Gwastadannas Farm had been our first camp on the 2022 Dragon’s Back race. Revisiting it felt significant, probably because of the emotions associated with that race, and that camp specifically.

For those who didn’t read my Dragon’s Back blog post at the time: after surviving one of the scariest experiences of my life up on the knife-edged arête, thrashing through the pouring rain as darkness fell, and then sliding precariously down the slippery descent from Gallt y Wenallt, I hoped for an oasis of calm and relaxation at Gwastadannas. Instead, I received an official reprimand for missing a dibber at Crib Goch, and found I’d arrived so late that I had to rush to eat to avoid disturbing my tentmates.

Thus, my memory of Gwastadannas was one of the more distressing in my running journey. Making some positive memories there was a subconscious goal of mine. Right now, I was aiming to DNF there, so that wasn’t looking too promising.

The climb up Cnicht started simply, then transitioned to a steep, rocky, hands-on affair. From above, I could hear Jan’s boisterous encouragement echoing around the mountainside. “Come on, get a move on!” “Where did you go? I’m up here!”

When I summited, I found him alongside two race staff, who were wearing tired smiles suggesting they’d never encountered a personality quite like Jan before. “Can you take him with you?” one of them joked. Ha!

Jan gleefully bounded back along the ridge to Gwastadannas, leaving me to my slower, rather more pained trot along this undulating, boggy terrain.

All the bogs were an increasing concern. My feet were deteriorating, and I didn’t know how that’d develop given another 10-20 hours of immersion.

All my issues aside, I had to admit, it was bloody beautiful up here on the Moelwyns.

I passed a runner powering up a climb in the opposite direction, and asked what he was up to, expecting he’d be looping out to Cnicht from PyG or Pen-y-Pass. He told me he’d just started a Paddy Buckley attempt. This made me feel even more dissatisfied with my own performance. Why oh why hadn’t I DNF’d back at Croesor?

Finally emerging from the ridge trail onto a road overlooking the valley, I could see Gallt y Wenallt on the south-eastern extent of the Snowdon Horseshoe; and beneath that, Gwastadannas farm and camping field.

As I approached Gwastadannas, runners from the UTS 50k and 100k races joined from the road facing me. The 50k’ers had run straight from Snowdon, while the 100k’ers were coming from Moel Siabod.

It might help if I explain the route from here. All of us would run south-west together down to Nant Gwynant. While the 50 & 100k’ers would veer off to climb straight back up Snowdon via the South Ridge, we’d continue to loop around Beddgelert, over Hebog, Y Garn, Nantlle Ridge, through Rhyd Ddu, and climb Snowdon via the Rhyd Ddu Path. We’d rejoin the 50 & 100k’ers at Clawdd Coch, 150m v+ shy of Snowdon summit, and thereafter the remainder of the race would be run together.

I didn’t know any of this at the time, and simply felt a bit overwhelmed by the presence of so many other people.

The checkpoint was heaving with runners, all seemingly far more awake than I. Within the big aid tent, there was an area with food (mainly crisps, fruit and Naak products) that was cordoned off for just the 100k & 100 milers. For the 50k’ers, Gwastadannas was only a drinks stop. I grabbed some fruit and sat on the chairs around the perimeter of the tent, observing the other runners.

A steady stream of 50k’ers were trying to enter the food section, but being rebuffed by a member of staff acting as a bouncer. Some looked none too pleased about this. These runners were 15km and 3h 45m into their race, only about 15 minutes ahead of their cutoff. Many of them were obviously suffering badly from the heat, and some had awful sunburn. I reflected that for many of these folks, this could be their very first ultra, on one of the hottest days of the year so far.

Sitting on my chair munching through melon, I didn’t feel too great myself. I was now 3h 30m behind my schedule. It was already a hot day, and would only get hotter over the next few hours. My throat was far from stellar, and I was still eating very little. Most of the carbs I was managing to consume were coming from a bottle of Tailwind.

In my favour, the next stretch down to Beddgelert looked simple enough on the map. Almost flat, broadly speaking. So I considered that DNF’ing here didn’t make any sense either. It’d be much easier to accept a DNF at CP9, with the significant peaks of Moel Hebog and Y Garn right ahead of me.

Dunking the Hat

The path down to Nant Gwynant was indeed straightforward and well-made, which if anything just focused my mind on how crap I felt. I passed lots of chatty 50k’ers, whose interest in the 100M race was heartening, but in my state I could have done without.

The last straw came when the narrow singletrack was blocked by a cow who’d decided the shade afforded by a tree would make a perfect resting spot. I stood there giving him a right bawling out, before leaping over him in a huff. While I didn’t know what a confused cow’s expression looked like at the time, I think I do now. It can’t be every day he gets a furious dressing down from a short bloke with a sore throat.

It was almost the hottest part of the day, and down in the valley it wasn’t just heat but humidity we had to deal with. Along with mild sunburn, I could feel the first signs of heat exhaustion creeping in.

Fortunately this section of the route tracked alongside the Glaslyn river, so whenever I saw an opening at the water’s edge that wasn’t already occupied by tourists, I dashed over and dunked my Saharan hat. It gave me a minute or so of evaporative cooling each time.

Eventually stone walls and buildings emerged alongside the river. I was entering Beddgelert, a picture-postcard little town from what I could see. I passed a riverside café, which sorely tempted me. Up ahead I could see a stone bridge crossing the river, where a few supporters had taken up residence. I heard Jan’s booming voice before I saw him.

I gave him the sitrep: SNAFU (situation normal, all fucked up). Nutrition terrible, hydration poor, overheating, tiredness increasing, feet permanently wet, and feeling crap. But on the flipside, the scenery was really lovely.

We entered CP9 at the village hall, where he started unloading containers of food onto a table. I stood looking on, just as confused as the cow from earlier. He obviously hadn’t slept. Instead he’d somehow cooked me salted & spiced new potatoes. Crudites. Guacamole. Dips. Then he presented me with a vegan Keralan pasty. Where on earth had all this come from? I just tucked in. It was bloody delicious.

Halfway through stuffing my face, I remembered I was possibly supposed to be DNF’ing here. That didn’t look awfully straightforward. Jan had prepared this incredible feast for me. Thanks to that, I’d soon be fully refuelled, rehydrated, and re-energised. No, I couldn’t DNF here. CP10, perhaps.

I changed socks again to give my feet a short break from swimming in water, and took a filter flask that I’d forgotten to pick up from my drop bag in Croesor. After almost 45 minutes (!), I headed back out into the heat.

I was now 5 hours behind my original schedule. There’d be no way to finish by the evening, as I’d originally intended. Even finishing overnight looked unlikely. Would I actually be able to checkout from my B&B on Sunday morning? While trotting along, I placed a call to the owner of the B&B, and managed to extend my accommodation. That was a relief. However long I took to drag myself around the course, logistically, everything would work out.

In my mind, that moreorless committed me to finishing the race, otherwise I’d just extended my accommodation for nothing.

So that was it then, the DNF was basically off. How did I get myself into this stupid situation?

The Nantlle Fiasco

There were certain sections of this race I’d been slightly trepidatious about from the outset. The diversion around Pen Yr Helgi Du was one, and the approaching Nantlle Ridge was the other. I’d heard mention of it a few times in the last couple of days. It was, apparently, a feisty little traverse. How feisty, exactly? The last thing I needed now was a Crib Goch-style scramble.

As apprehensive as I was about what was to come, I had to admit, the climb up Moel Hebog was as strikingly resplendent as it was accessible. Bedecked in bluebells under the warmth of the early evening sun, I couldn’t help pausing to soak it all in.

There was a fun little scramble up to the top, but when I turned right and saw the direct grassy descent, I grimaced. It was steep. At about 6500v+ into the race, that wasn’t what my quads wanted to see. I zigzagged my way down to limit the damage.

The next couple of fells were similar. The last had an extremely steep climb up, and another quad-wrecking descent. This whole ridge through to Rhyd Ddu is on the Paddy Buckley round; not an easy section to hammer out, I’d wager.

At this point, I was struggling with a few new problems, including chafing. This was probably due to my not keeping on top of things throughout the race as I ordinarily would, since I’d been planning to DNF.

So, with pain building and any time pressure relieved, I struck up conversations with other runners to distract myself & help the miles tick by.

The heat continued through the day, and aware of the distance remaining to CP10, I began to ration my water. So I was pretty chuffed when I passed couple of safety team members propped up beside a large boulder, offering a water top-up from a large water bladder. Spiffing!

I could see what looked like a rugged ridge up ahead, and wagered that was Nantlle, the source of my present angst.

A couple of runners I’d spoken to earlier were waiting for me at the base of the climb, which really confused me. In races, runners waiting for one another like this doesn’t happen - not where I usually am in the pack, anyway. It turned out they were confused about why I’d dropped back earlier, after showing some bursts of speed, and wanted to check I was okay. I grinned, and suggested they read my blog post later.

These runners were two friends, a male and female. The male was an experienced climber, and the female a runner who had attempted UTS before. She’d almost finished, only DNF’ing painfully close to the finish after suffering from severe sleep deprivation. She vaguely recalled Nantlle as being exposed and sketchy, which did nothing for my mood. Like I say, I really didn’t fancy tackling one of Crib Goch’s cousins today.

So, I made the calculated decision to hold myself back and stick with the pair. If this was to be a dodgy knife-edge scramble, then in my present state, and no longer caring about my time, I’d prefer to traverse it with company. With that decision made, the ridge turned into quite a chatty affair, though thick with trepidation on my part. I stuck behind the pair, always wondering when we’d reach the scary bit.

The scary bit never came. There was no exposure, nothing of any concern in fact. For the most part it was perfectly runnable. The latter section was indeed rocky and technical, but a decent route through was always pretty clear, and I could have moved really efficiently if I’d tried. Either I’d misinterpreted their warnings, or we just had radically different levels of comfort on terrain.

Emerging out onto the grassy side of the fell, I wished my Nantlle compatriots well and pulled away, trying to make up some time descending the eastern side of Y Garn.

I reflected on what’d just happened. I’d spent hours tentatively picking my way over a dangerous ridge that had turned out to be a nothing of the sort. In fact, it would have been really good fun had I not been worrying about what was coming next.

Originally, I’d predicted this stretch from Beddgelert to Rhyd Ddu would take me 3 hours and 30 minutes. Another runner had told me 4 hours was a common estimate for mid-packers. It’d actually taken me 6 hours.

I was pretty disgusted with myself. Jan had probably given up on me and gone home.

Supporters were gathered outside the car park on the A4085. I could hear Jan’s cheery, raucous welcome above all the others. Somehow, he was still not just still awake, but having a total blast. I reasoned he must be setting new records for the amount of coffee consumed without sleep.

CP10 was in the Rhyd Ddu Outdoor Centre. All I really needed was a water top-up; but with no time pressure any more, it made sense to use the opportunity to prepare well for the coming night, and graze on Jan’s buffet. I only had a simple up-and-over Snowdon before the next CP anyway.

After 20 minutes stuffing my face, I was back on the trails clutching a bagel and a couple of waffles. It’d be a wonder if I could physically haul myself up the mountain with all this food in me!

Approaching 40 Hours

Feeling pretty tired, and with no motivation to push myself (what for?), I settled for hiking up the Rhyd Ddu Path. In the process, I scoffed all my ‘real food’ and put my headtorch on, ready for my second night in Snowdonia.

Shortly afterwards, a large group of folks caught me up, screaming, laughing and jostling. They seemed to be supporters on a break, looking to bag a summit, quite possibly after a bevvy or three.

Having caught me up and surrounded me, they made no effort to move on past. So I found myself trapped amidst this chaotic cacophony of noise, raucous antics and blinding headtorches. After 35 hours, a tanked-up teenage knees-up wasn’t what my headache needed.

I tried slowing down so they’d move on, but those in front just slowed to match my pace. Instead, I decided to step on the gas and leave them behind.

I enjoyed a brief stretch of peace and quiet in the darkness, until the 50 and 100k’ers joined from the south at Clawdd Coch. We had a rocky ridge run to reach the Watkin path, and Eryri’s visitor centre, around which was a veritable hive of activity.

The night air seemed thick with particulate matter on the run down to Bwlch Glas. It felt like sand. Were we encountering one of those sandstorms blowing up from the Sahara? I couldn’t make head nor tail of it, so I stuck to nasal breathing, while wondering whether I was losing the plot.

From here, I had half of the Ranger Path to descend (which I had passing familiarity with), before splitting left onto a lesser path that led down to CP11. Here, I enjoyed the peace and quiet I was looking for again. Around me, I could see the traditionally UTMB sight of headtorches snaking up mountainsides. Glorious moments like these are why we run.

The lesser path that broke away from Ranger changed all that. Wet, overgrown and a bit of a hackathon, it had me moaning and groaning once more, eagerly looking out for anything down below that looked like a checkpoint.

Half an hour of sloshing through water later, I arrived at CP11, a classic UTMB-style marquee in a field next to Cwellyn lake. I expected I might not find Jan here; after all, not even Jan could crew through two nights straight with no sleep. So I was amazed to find my dependable one-man crew here, dutifully laying out the real food buffet he’d manifested through magic and alchemy.

For the first time I could see he looked tired, and he divulged he was going to head to sleep afterwards. This was the last place he was permitted to crew me before the finish anyway, so he’d literally done the whole thing without a break. He was the one who deserved a medal!

I grazed on potatoes and guacamole, in no great rush to get going. There didn’t seem any point in rushing things; this venture had ceased being a race a long time ago. In the end, it was another lackadaisical 30 minute turnaround.

I set back off on autopilot. There was only 8km and one hill to CP12. After that, just 16km and one hill to the finish. It didn’t get much simpler than that.

Within a couple of minutes I’d dunked my freshly dried feet back into a huge puddle, and picked up a singletrack through a muddy wood. Fallen tree trunks littered the path, piled high in places like walls. It was slow progress until it broke out onto an undulating grassy plain, from where I could see headlights ahead of me snaking up Mynydd Mawr. This was another atmospheric sight that brought a smile to my weary face, one that made my decision to continue seem worthwhile.

Unlike last night, the temperature was dipping fast. As I began the ascent, the wind really picked up, so I sheltered beside a rock to don a windproof and beanie. It seemed like a long climb up to the nondescript rocky summit. Covered in mist, it had a slightly eerie quality to it.

The descent down loose scree was fairly steep, which I tried to float down as freely & effortlessly as I could, despite the tightness in my quads.

It was 3am when I trundled into Betws Garmon. The route took me into a motorhome campsite, where everyone was surely tucked up soundly in their beds. I turned down my headtorch, and did my best not to disturb anyone.

It transpired the final checkpoint, CP12, was in a marquee just adjacent to these sleeping campers. So there’d be no raucous last checkpoint party here, then.

I found a real motley crew of runners hiding out in this subdued marquee. Most looked thoroughly beat, but there was one who was upbeat, sharing information on the route ahead based on his recces. According to him, there was a circuitous route leading to a wood that he described as “really shit”. However, the last 5k was a road run where we could really “open up the taps”. Based on the expressions on the faces of these runners, I hypothesised this tap might not produce a deluge so much as a trickle.

While I was there, a couple of runners who traipsed in out of the night looked like they were really struggling. I tried my best to perk one up who looked severely despondent, but that was going to take more than some comedic anecdotes and words of encouragement. Maybe I wasn’t best placed to be giving motivational speeches anyway.

I downed some tea, bananas and crisps, and sorted my fluids. 25 minutes had flown by, and I’d been socialising for far too long again. It was time to get it done.

Out the campsite, the route took me up into yet another wood. It was tricky going through here, with thick mud sucking me into the ground, countless streams and deep channels needing navigation, and more fallen trees blocking my path. Entering my 45th hour without sleep, the pitch darkness under the tree canopy did me no favours, and I could feel tiredness setting in.

As I emerged from the mud-wood, for the second time on this expedition, I could see a new day was dawning. The light from my my headtorch flashed a few times to warn me of its impending death. I’d only need it or another 10 minutes or so, so I resisted changing torches.

I knew I was getting close to the finish now, and I even recognised snippets of the route from a run I’d done some years ago. Those little moments of déjà vu felt both exciting and disconcerting in equal measure, as I couldn’t shake the niggling sensation that I could be in a dream…

Only some 10km and the summit of Moel Eilio stood between me and the finish, assuming I was indeed in the land of the living. While these thoughts flitted around my addled brain, a rock ahead of me morphed into an animal, and a wave of tiredness flooded my body. Within seconds, my eyelids closed, and I found I couldn’t reopen them. My brain was shutting up shop. This was it, I realised. My body was done.

Should I be surprised? I’d battled through poor fitness, illness, that interminable DNF debate, dehydration, sunburn, heat exhaustion, the inability to eat for half the race, chafing, consistently wet feet, and worries about the technicality of the route ahead. I’d run 158km, climbed 10km, and been awake for 46 hours and counting. Now it was all catching up with me, and I couldn’t see where I was fucking going.

This felt just like the Spine. It was early on, approaching Malham CP1.5, when I couldn’t keep my eyes open. I’d staggered, zigzagged, instantaneously fallen asleep and woken up as my body collapsed to the ground like a puppet. Well; bingo, here we go again.

The thought that I’d been through this before was the one ray of hope I could cling to. I forced Tailwind and mouthfuls of sugary chews down my throat. I took off some clothes to make myself cold. Then I put on extra clothes to make me overheat. None of it helped.

I physically held my eyeslids open, and I staggered on, flitting into and out of consciousness, stumbling over the rutted trail and veering uncontrollably into the undergrowth.

After the trail turned back on itself to head up Moel Eilio, as much as I was trying to physically hold my eyes open, I just couldn’t. They snapped firmly shut. Then I couldn’t see. I had to stop.

I dumped my pack on the grassy hillside, and collapsed onto it. Arms crossed, I let out a loud sigh. 160km done. I was already most of the way up the last peak. I only needed my broken body to transport me another measly 7km, mostly downhill.

But my eyes were closed, and my brain was shutting down. I had to sleep.

“If I hadn’t been ill” thoughts flooded the few active neurons in my brain. If I hadn’t been ill, I’d have thought to pack some caffeine or chilli. I’d have fuelled and hydrated consistently. I’d still be treating this as a race. I’d have finished fucking hours ago, for Pete’s sake.

If this, then that. If that, then the other. Meanwhile, I was falling asleep. I shook my head. I was out of ideas, and out of shits to give. I should have DNF’d back at CP9, 8, 7… 2... Hell, I should never have started.

Was sleeping on the course permitted, or was that a mountain rescue + DQ offence? I hadn’t looked into the rules. If it came to it, I’d call it in and DNF myself here, I decided. I mean, it looked like it was going to be a lovely morning. What better place to DNF than on the side of this grassy fell, with these glorious views, snuggling up and getting some much needed rest. I laid my head on the grass.

I could hear someone approaching. I forced my eyes open, and with some effort I managed to bring the blurry image into focus. There was another runner, climbing up the grassy path. My first reaction was embarrassment to be caught splayed out on the ground, wrecked. But then a lightbulb pinged in my head.

Talk to him.

I leapt to my feet and whipped my pack onto my back. Trying to sound as nonchalant as I could, as though I’d just stopped to tie a shoelace, I cried out “Hey, how’re you going chap? Cracking morning isn’t it!”

And with that, we struck up a conversation that jolted me back into the land of the living, and kept me going all the way up Eilio.

As we approached the top, my companion glanced at my race bib to catch my name, and in so doing spotted I was on the 100 mile race. He did a double-take.

“Oh Christ; I’m so sorry, I’ve been holding you up!” he exclaimed, visibly anguished by the thought that he might be delaying my progress. Despite my reassurances, he stood his ground and urged me on, clearly believing that I was only accompanying him out of sympathy. I just laughed, explained the pickle I’d been in, and how his company had saved my race.

In a way though, I realised he had a point. After that chatty hike, I was feeling wide awake and re-energised. I didn’t need to be traipsing around any more. It was time to part company.

Bidding my compatriot farewell, I shot off over the undulating ridgeline feeling like a man reborn. I loved the fast grassy descents, and enjoyed powering up the climbs. For the first time in a couple of days, I felt like this was a race. A race. Remember those? It sounded super fun!

I managed a few overtakes, and got myself into a battle with a runner who seemed determined to retake his place. That wasn’t going to happen though, because I was racing now. Moreover, this was the endgame, the final 6k or so. I don’t cede places at this stage of a race.

Foel Goch was the last mini peak, after which it would all be descent. I allowed gravity to carry me down the steep-ish fell, until I shot past something pretty crazy. A runner was descending the trail barefoot. I questioned my own sanity; but no, there he was, genuinely barefoot. I shouted “that’s amazing!” back at him, but still couldn’t quite believe it, so I called it out a few more times.

Later, I learnt this was Ivan Hrastovec. A runner with a UTMB index of 821, he’d recently taken to running big races entirely barefoot. A race like SDW100, I could just about imagine running barefoot; very slowly, after many years of practice. But UTS, with consistently unforgiving rocky terrain? That’s another level. That’s impossible. At least, I’d have said it was, had I not witnessed Ivan doing it with my own eyes.

Anyway, that was it. The fell popped me out onto a stony road which transitioned into a tarmacked running superhighway. It hugged the side of Foel Goch, overlooking a valley backing onto Snowdon. I could see Llanberis emerging ahead, and focused on maintaining a good pace to the finish. The route dropped down into the valley, to rejoin the route I’d run out on almost two days ago.

I gave that final descent and run through Llanberis everything I had. Approaching the slate museum, I managed one last overtake, and gave a wry smile as I passed under the UTMB arch.

I felt nothing as I received my medal and put on a smile for the camera, because this wasn’t really a finish. This was something else, a perplexing 42 hour aberration born out of intransigence, or indecision, or… I racked my brains, trying to articulate it.

There, I’d hit upon it. This aimless 42 hour exercise in endurance was a DNDNF. A Did Not Did Not Finish.

Runner Without a Cause

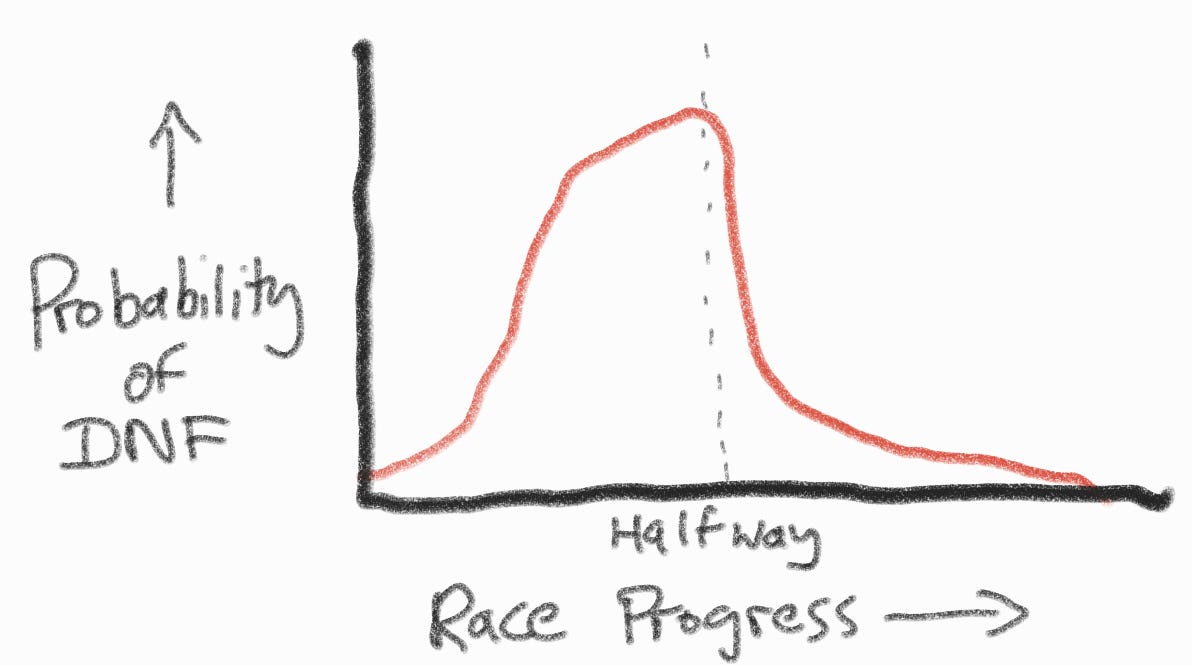

This 100 miler had one of the highest DNF rates of any race I’ve run, 62%. To put that in perspective, it’s higher than the Winter Spine. The only major race I can think of that it’s comparable to is Dragon’s Back.

So, an awful lot of people dropped out. Why didn’t I?

I left it to circumstance and judgement. The problem with this strategy becomes clear when you consider the whole point of an ultra is to push your limits and grow as a person. Unless I broke a leg, got hypothermia or fell down a gully, I was never going to DNF on a strategy like that.

I shouldn’t have started, or I should have prearranged an exit point.

Maybe one day I’ll go back and do UTS properly, maybe I won’t. Whatever I do, I’ll be sure to run races only when fighting fit from now on. For me, while races are to be conquered, they’re also to be competed & enjoyed. Conquering alone doesn’t cut it.

As I close the curtain on the final act of UTS 2024, I hope I’ve given you an insight into how the lack of a clear plan caused a series of (in)decisions that led to my finishing a race I had no intention of completing, and would have done better not to start in the first place.

I doff my cap to my friend Jan’s awe-inspiring effort crewing me over 42 hours straight, while also running up mountains, cooking buffets and encouraging literally the whole field. The poor guy only came to Wales to spectate! Head over to Savage Trails on Youtube to be uplifted & inspired by his quintessentially epic, continent-scale adventures - you’ll see what I mean.

I am now the (not very) proud owner of a shiny UTS medal. Every time it catches my eye, I furrow my brow and give a wry smile. A medal for kicking the proverbial can down the trail for 42 hours. A medal for unpreparedness. A medal for a rebel without a cause.

A medal for a DNDNF.