The Spine (Part 3 of 7)

Razor Fields: Hebden Bridge CP1 to Hawes CP2

This post follows Part 2: Pride Comes Before a DNF

In the Hebden Bridge checkpoint, a few other runners sat slumped in their chairs, looking tired, confused, and listless.

I, on the other hand, would be purposeful and efficient, because in my drop bag was my laminated checkpoint checklist! I dug it out, and metaphorically patted myself on my back. It really did look like a professional plan, with all its bold, complementary colours and well-considered formatting. It clearly laid out everything I would need to do here. All I had to do was follow the instructions, as simple as A-B-C.

Item #1 was “charge electrical devices”, something about which I needed no reminding. So I found one of my powerbanks, plugged in my watch, and then wrestled with the stupid thing as it stubbornly refused to charge. A bit of investigative work later, and I’d proved that my charging cable was completely kaput. “That’s just spiffing”, I grumbled.

The rest of my checklist proceeded in a similarly frustrating vain. Every item proved to be problematic, irrelevant, or was obviously in the wrong priority order. I rested my head in my hands and let out a loud sigh. Crap checklists and annoying admin. I was too tired for this.

“Was there food?”, I asked the volunteers, hopefully. The food was downstairs, I was told; but since they needed to keep the room clear for other runners, I’d have to pack all my stuff away in my drop bag first. That really threw me, because I’d only just taken everything out.

I unceremoniously stuffed my dumb checklist back into the depths of my drop bag, and stared blankly at my charging electrical devices. All the adrenaline had gone, tiredness was catching up with me, and for the first time in a race checkpoint I seemed to be stuck, unable to make a simple decision as to what to do next. I faffed around with whatever I could easily lay my hands on. Ostensibly, I was making very important kit decisions of the utmost significance; but frankly I didn’t decide a single thing. It was just mindless procrastination.

Eventually, I summoned the willpower to repack my gear and move downstairs to the dining room, an act that felt just expeditionary as my entire journey to Hebden.

The dining room was small, but a hive of activity. The runners here seemed more switched-on, multitasking between eating, drinking, charging devices, and letting their feet air. I worked my way through a couple of servings of pasta with vegan bolognese, and washed it down with another cup of tea.

When I finally left Hebden checkpoint, I calculated I’d spent 90 minutes there. Doing what, I honestly couldn’t fathom. “I didn’t want to rush things, but I’ll obviously have to get quicker”, I told myself, trying to sound reassuring.

It wasn’t long before I was back on those rock-hard frozen farmer’s fields I’d taken a dislike to earlier. The unevenness of the ground was likely from cattle and sheep traipsing over them during muddier periods. When that churned-up, jutting out ground froze hard; golly, it wasn’t pleasant to run over. My feet were hating every step.

Over the course of the next few miles, their health rapidly deteriorated. My left foot grew really painful, particularly around the ball of my foot. It was affecting my gait, which was a concern; but aside from anything else, it was bloody annoying.

At this point, I should explain: I don’t do anything special to my feet. I don’t tape them. I don’t anoint them with magic creams. I don’t file/shave/polish them, coat them with Danish oil, or whatever on earth people do. I just train in fairly uncushioned shoes, and my feet generally handle what’s thrown at them just fine. Maybe it helps that I’m tiny and weigh the same as an apple, I don’t know. Anyway, this was clearly not working today.

Should I stop and do something, I wondered? But what? Taping is what people usually do. What would I do with the tape, exactly – mummify my foot with it? I hadn’t a clue. Regardless, from a practical perspective, it was far too cold to be stopping and cutting shapes out of glorified parcel tape with a dinky pair of scissors.

My problems multiplied when my right shoulder developed a problem of its own. The pain built to such a crescendo that I had to stop to rip my pack off. Alarmed, I performed series of shoulder rolls, arm circles and some self-massage. The combination calmed it down sufficiently that I could pause for a break.

Leaning against a fence, I gazed out over Walshaw Dean Reservoir, reflecting. Hardly 50 miles into the race, and here I was. Inexplicably tired. Surprisingly cold. My feet were wrecked. My shoulder was buggered. My pack was on the ground, and I was immobile. I’d probably never been in such a bad situation in a race before. At this rate, I was odds-on to DNF, and sooner rather than later.

I made some adjustments to the straps on my pack, in an effort to rebalance the load away from my damaged shoulder. Tentatively, I tried putting my pack back on, and found I could just about tolerate it now. So I started walking toward the next objective, CP1.5, a ‘monitoring point’ at Malham Tarn. I reintroduced some gentle running, and tried to build back into a rhythm.

But I couldn’t. The pain in my left foot was telling me to stop, and my right foot was developing a similar problem, centred around its big toe. The particularly worrying fact was that foot problems don’t improve over the course of a race. They only get worse.

My shoulder kept flaring back up too. Was that going to settle down eventually, or worsen with my feet? That actually had the potential to be the bigger problem, because I obviously needed to be able to carry my pack.

To make matters worse, it was getting cold. Really cold. Way beyond what I’d experienced at the start line in Edale. And the night was only just getting underway. How cold would it be in a few hours? I didn’t even want to think about that.

This race, for what it was, was beginning to look hopeless. How long could I even continue like this, hobbling around in these temperatures, like a three-legged amputee Sphynx cat trying to survive in the arctic tundra?

I contemplated calling race HQ to tell them I was DNF’ing. I may as well do it sooner rather than later, before I slowed so much that I risked hypothermia. I could turn around and return to Hebden Bridge, that would be a good plan. Or maybe I should try to keep going, perhaps I’d even be able to reach CP1.5 at Malham Tarn. That sounded slightly better than DNF’ing at the very first checkpoint. I could call my brother and ask him to collect me from there. Could you even drive to Malham Tarn? I had no idea where that was. Or where I was, for that matter.

I couldn’t settle on any single course of action. So I just hobbled on, deferring the inevitable DNF, and hoping that I could stave off hypothermia while moving as slowly as I was.

Nothing seemed to be going in my favour, not even the waymarking. It was terrible along this stretch of the Pennine Way. Time and time again, I had to backtrack in search of the right route. There were so many styles, gates, bogs, and that dastardly rock-hard frozen ground was everywhere. I was getting so fed up. And still, the temperature kept dropping. I don’t know how many degrees negative Celsius it was, all I knew is it was freezing. As in, as cold as I’ve ever experienced freezing.

Amidst all the trouble I’d had, I realised I’d completely neglected my hydration. I took a sip from my softflask, but no water came out. All my softflasks had frozen.

As I dropped down into the town of Cowling, I passed a little stone shelter beside the road. Spotting an opportunity to improve my situation, I paused to pull on an extra fleece.

My mitts were only off for a couple of minutes. It was when I tried to pull them back on that I realised how painfully cold my hands had become in that short time. I balled my hands up under my Fury gloves and Prism Dryline mitts, but the pain was now eyewatering. I trotted through Cowling and back out onto the frozen trails, willing that pain to lessen, and my hands to defrost. While I didn’t know much about frostnip and frostbite, I figured I was getting a crash course.

I was too cold to sustain these conditions for much longer. I’d heard that Lothersdale Tri Club put out some sort of mini aid station somewhere near my location. I had to reach it, and soon. Even if it just turned out to be a table with a few cups of ice on it, I’d appreciate there being someone standing there, momentarily enduring these conditions with me, proving it was indeed possible to survive these temperatures. I was willing that Tri Club ice table into existence. It had to be here somewhere. I was freezing to fucking death out here. Where was it?!

My mileage was probably a bit off due to the poor waymarking, and the backtracking I’d had to do. After what felt like an eternity, I descended into the town of Lothersdale, and finally found the Tri Club. There was a gazebo with a BBQ sticking out of the side of it, and something that looked like it could be an inflatable first aid tent.

Before I could make much sense of it all, a cheery chap asked me what I’d like to eat. Upon hearing I was vegan, he offered to cook me a courgette and mushroom roll. (Now; when you’ve been in survival mode, then someone offers you a courgette and mushroom roll – that is transformative!) Then, he ushered me inside the inflatable first aid tent. Worried they might be looking to DQ me for hypothermia, I paused briefly, before following him inside. But I wasn’t getting pulled for medical examination, and this wasn’t an first aid tent. It was heaven on earth.

Chairs were dotted around the perimeter, covered in emergency foil blankets and actual warm, fuzzy blankets. Coloured lighting created a sensation not unlike a nightclub, and heaters had the space nice and toasty. A buffet table laid out some grazing options, and as I slumped into a chair, I was handed a cup of tea, shortly followed by my delicious vegetable roll. I couldn’t believe it. This was my brand new favourite place in the entire world.

I used the tea to defrost my water bottles, wolfed down my delicious & nutritious roll, left the Tri Club a donation, thanked everyone I could find, and steeled myself to leave this haven of warmth and restoration. Getting going again was bound to be a challenge.

There was 15km to the next mini-milestone, the town of Gargrave, which had a Co-op. That didn’t open until 7am though, and I’d be passing through long before then. Meanwhile, I was back out in the arctic temperatures, trying to survive in these brutal conditions. I was wearing nearly everything I had: all my hats and hoods, and even my full face balaclava.

Out of Lothersdale, the Pennine Way reverted to form. It was back to constant undulations, styles, gates, poor waymarking, and those sodding churned up farmer’s fields. The ground protruded from all directions, jutting into my feet like razorblades. The soles of my shoes offered scant protection, and my feet were aching something awful. They must be blistered to buggery and beyond.

“The number of problems I’ve got is intractable, and the severity of each problem is growing”, I reported into my handheld dictaphone, in a deadpan tone, rather like I was reading the nightly news. “Realistically, I’m not finishing this race, I know that. It’s just a question of how much pain I endure until I surrender”.

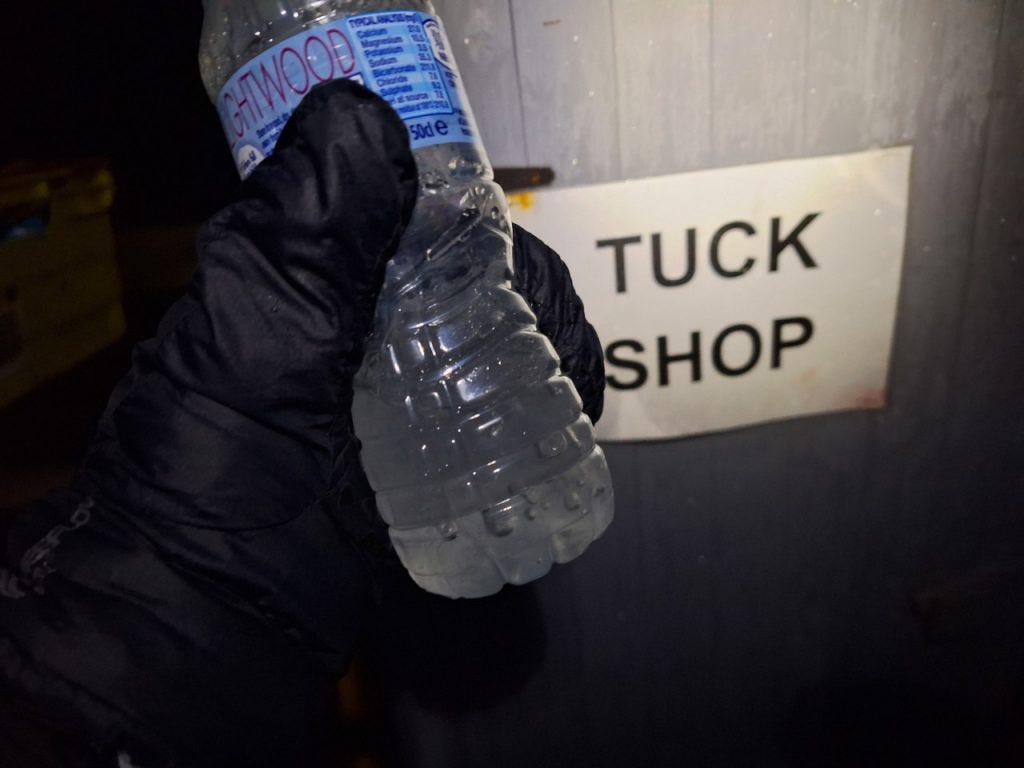

My water bottles had refrozen within minutes of leaving Lothersdale. So when I passed the Cam Lane self-serve tuck shop, serving a wide range of cold and frozen drinks, I got quite excited. I popped some money in the tin, picked up a bottle of water, twisted off the cap and took a sip. Only a few drops of water came out, then the bottle-sized block of ice shifted and bumped into the top of the bottle. Chuckling in resigned bemusement, I dropped it into the bin beside where I’d bought it.

Between the continually poor waymarking, styles, broken gates, and my personal nemesis – the churned up razor ground – it took me approximately forever to reach Gargrave. By the time I found its town centre, it was actually past 7am, and the Co-op that I was sure I’d miss by a couple of hours was already open. I wasn’t sure whether I should be happy about that. I paused in a public toilet to put on the very last item of clothing I had, my Montane Fireball jacket, and then entered the Co-op to buy some falafels.

While I munched through my falafel balls in an outdoor shelter beside Gargrave’s village green, I listened in to a conversation between another runner and a member of the Spine Safety Team. She was wearing everything she had, couldn’t get warm, and didn’t think it’d be safe to climb Pen-y-Ghent in these conditions. As I left, she was asking to retire. That sounded very sensible, I thought. I should really do the same.

I continued, but I still wasn’t sure whether I could make it to Malham Tarn. “I’m obviously not going to finish this race. That’s just abundantly apparent. It’s impossible”, I bemoaned into my dictaphone. But nor could I stop unless I had to. Aside from my own expectations, too much was riding on this.

It was winter in Palestine too. The Palestinian people were freezing, but with most of their homes bombed to rubble, they had nowhere to go. Not just for a few nights, but permanently. They were out of potable water, without even any ice to fallback to. There was precious little food. They were out of everything but rubble and bodies.

I was carrying a Palestinian badge, and a Palestinian flag would be waiting for me at the finish line. I had to get to that finish. I had to raise the flag. I had to. But to do that, I also had to survive.

I was mightily relieved when the sun rose, which took the edge off of the cold, and made the situation feel less life-or-death. Weirdly, though, with the rising of the sun, I grew ever more tired. I was only a day in, but I was already starting to experience full-blown sleep deprivation.

I started zigzagging, physically unable to maintain a straight path. Then I dozed off while I ran. My eyes closed, I began to fall, and the falling sensation woke me back up. I’d experienced this before in a track 100 miler, but that didn’t make it any less worrisome. Especially out here, in negative whatever.

So it went, microsleeping and jolting back to my peculiar reality every 10 seconds or so, in a semi-conscious zombified stupor. I began to hallucinate. Figures, faces, shapes and colours materialised alongside me. I struggled to distinguish between what was real and what was not.

I grew more conscious when I stumbled into the picture-postcard town of Malham. The B&Bs and pubs looked real enough, as did the photographer standing in the middle of the road, incontrovertible proof of which exists below.

Markedly more compos mentis now, I toddled off in a much improved mood toward the stunning geographical wonder that is Malham Lings.

Tiered limestone escarpments rise from the valley, surrounded either side by terraced fields broken up by irregular drystone walls. It was quite a vista from down in the valley, but it got even better when I summited.

The organic rock formations up here stretched out far before my eyes. I’d never seen anything quite like it. This was a massive playground for runners. My aches and pains receded to the back of my mind, and my tiredness completely forgotten, I revelled in skipping over these curious rocks with childlike abandon, not particularly caring about whether I was on route or not. It was joyous. All the troubles I’d endured had been worth it, I felt, to experience this moment of wholesome, life-affirming bliss.

Alas, as much as I wanted to, I couldn’t spend the day playing games. I had to break away from this geographical wonder to track the path north, up the grassy wind tunnel to an expansive plateau, surrounded by hills on all sides. In the middle of the plateau was Malham Tarn; a stunning, navy blue glacial lake. It reminded me of the lakes in Aigüestortes national park in the Pyrenees.

I battled through headwinds gusting across the plateau, toward the impressive mansion house I could see across the lake. I located CP1.5, the Malham Tarn monitoring point, in one of its outbuildings.

The monitoring point was just a small room, but it was a hive of activity. There was a free chair right beside the entrance door, where a volunteer promptly delivered me a steaming mug of tea. I put my watch on charge, and watched everybody else tucking into their dehydrated meals. I hadn’t thought to bring one, so I just gazed lustfully at theirs, occasionally flicking a Veloforte chew into my mouth to satiate me while I finished my tea. Feeling a bit better now in the more survivable daytime temperatures, and with the pain in my feet at tolerable levels, there was no question of my retiring here as I’d thought earlier on.

When I spotted the volunteer was idle, I asked him when the frontrunners had arrived. His face lit up at the prospect of talking about something other than hypothermia, hot water and knackered feet. He puzzled for a moment as he worked backwards through time. About 11 hours earlier, he concluded.

Eleven hours. Bloody hell, I was slow!

There was still a marathon to go to the Hawes checkpoint. That meant I’d better get going. My feet were pretty sore, so I deployed my poles to take some of the weight off my blistered soles.

My mindset was shifting. I was thinking ahead, considering what I’d change at the next checkpoint. I’d have to treat these blisters somehow (another thing I had zero experience doing). I might even ask a medic for help, I mused. Perhaps I’d try a larger pair of shoes, and two pairs of socks. I’d need more layers as well. I had a second pair of Prism Drylines in a larger size, maybe it was time to double-mitt!

Looking around me, I could see how spectacular the fells were up here, wherever ‘here’ was. I figured I might be in the Yorkshire Dales.

One particularly distinctive fell caught my eye. Flat-capped and robust, I would later learn this was Pen-y-Ghent. There was quite a fun little scramble to be had up its southern face, before a hard left at the summit to face into the westerly wind. Whilst fairly good fun, my poor, aching feet didn’t appreciate the fast & stony descent. I could feel my blisters, and with every little stone that jutted into my sole, I could imagine them preparing to burst. Goodness knows what I’d have to deal with at Hawes.

It was one long drag to that CP. My moustache was frozen, my water was frozen, the churned up farmer’s fields (oh yes, them again) were most definitely frozen, but I was at least less frozen than I’d been during the night.

I really enjoyed the last meandering descent through moorland from Dodd Fell down into Hawes. The final stretch to the CP, a fiddly journey through its residential streets, amongst houses, cars and normal daily life, felt pretty bizarre. This took me back to Dragon’s Back, where after days of navigating remote Welsh mountains and bogs, I’d pop out into a little town or larger city, and find all the commotion a bit overwhelming. Oh, for the simplicity of life in the fells.

As I climbed up the high street, searching for the youth hostel, I knew I had some serious business to attend to. The first priority would be to take my shoes and socks off, and air my feet. Then I needed to assess my blisters. Depending how bad things were, I might need the help of a medic, since I hadn’t a clue what I was doing in the feet department.

Also, after all that sleeprunning earlier in the day, I needed to get some decent shut-eye – a solid 90 minutes, I reckoned. Plenty of food, too. And I was really dehydrated. After all, my softflasks had been frozen for most of the last 100k.

So I needed everything, basically. A full service, MOT and a new set of tyres.

I clasped my Palestine badge in my hand. I was going to get myself back out of this checkpoint. Of that I was certain.

Continue reading: Part 4: Ice Goes Better With Whisky

The post The Spine: Razor Fields appeared first on The Trail Explorer.